Women are nearly three times more likely to suffer from common mental health disorders than men, and this risk is highest during their reproductive years. Hormonal fluctuations and symptoms associated with the menstrual cycle are likely to form complex, multidirectional associations with mental health. However, the intersection of menstrual and mental health is severely under-researched leaving millions of women with limited support and treatment options.

Below, we outline some of the ways in which menstrual and mental health could be linked.

Menstrual disorders

Symptoms of menstrual disorders, such as abnormally heavy or prolonged bleeding (menorrhagia), pelvic pain (dysmenorrhea), irregular cycles and menstrual cessation (amenorrhea), are associated with lower quality of life and wellbeing, non-attendance at school and work, and higher rates of mental health disorders.

Stigma and a lack of knowledge about what is ‘normal’ means menstrual disorders are often under-reported and under-diagnosed, particularly in low and middle income countries (LMICs), but they affect a large proportion of the population. For example, in LMICs, one study found that 5-20% of women experienced period pain that prevented usual activities. In the UK, 5% of women aged 30-49 years (that’s over 439,380 women) consult their GP each year due to excessive uterine bleeding.

The association between menstrual disorders and mental health is likely to be extremely complex, involving interactions between genetics, reproductive hormones and other physiological processes, but also environmental factors including lifestyle and social, political and structural influences on health and wellbeing, which will vary between high income countries (HICs) and LMICs. The association is also likely to be bidirectional. We already know that psychological stress can impact the menstrual cycle, causing changes to menstrual cycle features like heaviness of bleeding and regularity, as well as amenorrhea.

Menstrual health management

Access to safe, clean facilities, affordable menstrual products and sexual and reproductive healthcare are important factors in shaping women’s experiences around menstruation, and unmet menstrual health needs can have significant impacts on mental and social wellbeing. Taboo, stigma, and shame associated with menstruation can compound effects of these unmet needs on menstrual health. Most menstrual health management interventions are focused on providing menstrual products to individuals, but do little to tackle the structural and societal factors that reinforce menstrual stigmas and create barriers to menstrual health (Thomson et al., 2019).

Mental health over the menstrual cycle

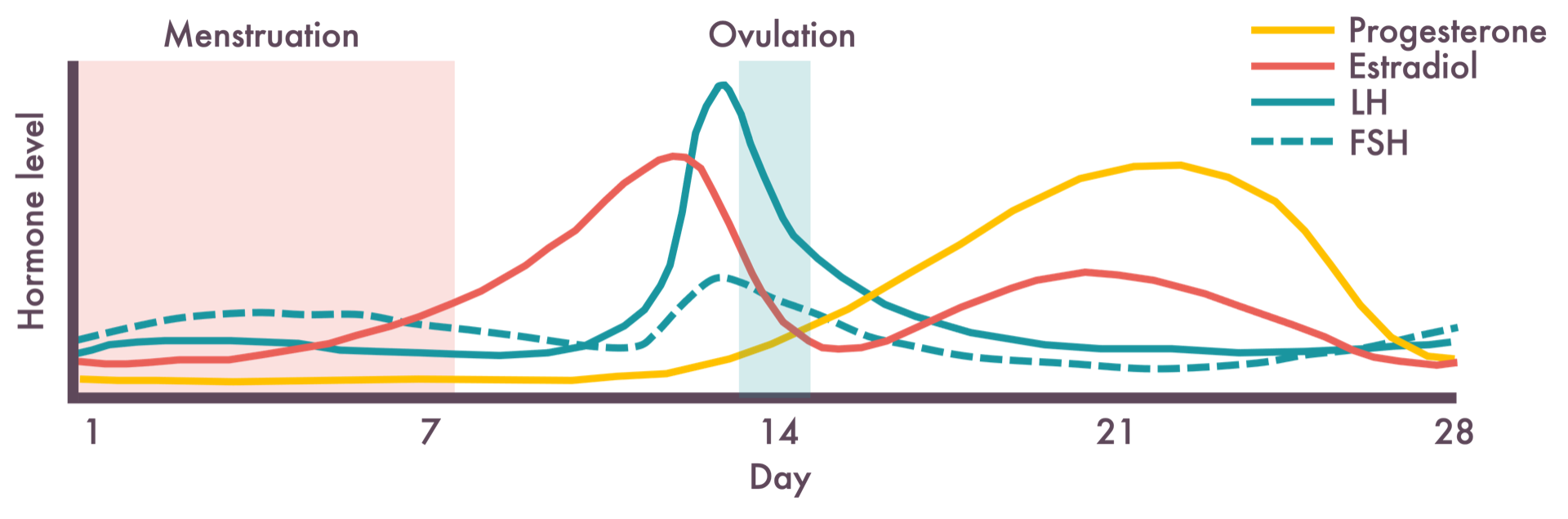

Reproductive hormones, like oestrogen, progesterone and gonadotrophins (LH and FSH), fluctuate throughout the menstrual cycle, and this can have pronounced effects on physiology, mood and wellbeing. Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is a set of symptoms that often occur about a week or two before menstruation (in the luteal phase of the cycle), and can include bloating, breast tenderness, swelling in hands and feet, food cravings, difficulty sleeping, as well as changes to mood and feeling upset, irritable or anxious. Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) is a mental health disorder that can impact a person’s ability to work, socialise and have healthy relationships. PMDD patients may experience suicidal thoughts premenstrually.

A better understanding of the mechanisms linking the menstrual cycle to mental health could help to identify women who might benefit from woman-centred psychological therapy (focused around self-acceptance and self-care) or hormonal treatment rather than interventions traditionally used to treat mental health issues, like antidepressant medication.

Menarche

The first occurrence of menstruating is called menarche. During this time, huge hormonal changes can affect mood and mental health. It can be a confusing time, and social stigma and taboo around menstruation can make important conversations difficult. Early negative feelings and experiences around menstruation could act as a blueprint for future, so quality education at this time (for menstruating adolescents and their non-menstruating peers) might help to reduce confusion and stigma, and improve mental wellbeing.

The average age at menarche varies significantly by geographical location and demographic factors like ethnicity. An earlier menarche has been linked to an increased risk of depression in adulthood, but the mechanism is unknown. It could involve a biological predisposition, but psychosocial factors and experiences in adolescence are also likely to play a role.

Menopause

The other end of the female reproductive life course is marked by the cessation of menstruation at the menopause. Hormonal changes around this time result in a wide range of physical symptoms including increasingly irregular menstrual cycles with changes to the duration and amount of bleeding, as well as symptoms like hot flushes, sweating, vaginal dryness and insomnia. Psychological symptoms are also common, including anxiety, depressive mood, irritability, mood swings and loss of libido. Cognitive symptoms include an inability to concentrate and poor memory. All of these physical and mental symptoms can affect a woman’s ability to have a good quality of life, to socialise, maintain relationships, and work, all of which is all tied up with good mental health.

Recognising and understanding the link between menopause and mental health is important for helping peri-menopausal women and their families and friends make sense of these changes, which are often completely normal and not do not indicate any kind of pathology. If healthcare providers were better able to predict which women were most at risk of experiencing mental health issues around menopause, they would be able to offer extra support to them. A better understanding of the biological and social factors that cause some women to suffer with their mental health at this time would help in the development of new treatments and strategies to lower women’s risk and improve their mental health.